A Shape Poem by any other name smells of breaking poetic rules.

Our 8 January 24 post introduced a rare variety of poetry – the Shape Poem, variously called visual poetry, calligram, and pattern poetry. In that post, we looked at animal butt poems, a badly drawn candle poem, a love poem with heart shapes, plus some examples of poetry that create meaning and effects by taking a traditional text (no picture shapes) and twisting the words in all directions: up-down, right-left, repetitive, side to side, top to bottom, upside down, and other words and shapes as far as imagination and courage takes the poet. It doesn’t hurt if the poet has a smaller than average ego to withstand the naysayers that lift their noses into the air, and haughtily proclaim, “That ain’t poetry!”

To review from 8 January, the Shape Poem is an arrangement of words on a page into forms, figures, silhouettes and/or patterns that reveal an image that of necessity partners with the meaning of nonlinear text which is amalgamated with the shape.

Visual poetry uses the page as a canvas for words that visually represent themes, subjects, or sentiments in words that would make sense if they were in linear presentation; however, the Shape Poem in its variety of shapes and forms challenges the reader (and viewer) much more than many more conventional poems.

Concrete poems are objects composed of words, letters, colors, and typefaces, in which graphic space plays a central role in both design and meaning. Concrete poets experiment boldly with language, incorporating visual, verbal, kinetic, and sonic elements.

The beauty of the visual format lies in the poet’s ability to mark, prescribe, or record process; the replication of shape; or the simulation of movement. It can also present the material in a way that leads to other meanings or implications that aren’t reflected in the words themselves. As Johanna Drucker notes in her book, Figuring the Word, the page serves "as a vocal score of tone or personality."

Furthermore, these visual poems are an artistic blend of the literary and the visual arts. Readers experience a shape poem via its words, typography, and the visual representation of the poem’s subject. In this type of visual poetry, the meaning of the poem is enhanced by the shape of the poem itself. Scroll down quickly and simply notice when you come across a picture with words mostly inside it, although at times, the words themselves are crafted into a picture – see “The Mouse’s Tail” and “Swan and Shadow,” below.

Rules? Well, like a recent workshop delivered by yours truly, part of the fun is to break rules in the name of beauty, laughter, and gravitas. Shape poems can but rarely rhyme. The meter is varied, often according to the demands of the shape rather than the word choices or meter. Line lengths (and syllables) depend on the dictates of the shape. Common themes are nature, seasons, relationships, often doused with humor. Finally, in case it isn’t obvious enough, Shape Poems have no rules other than they be identifiably a poem. A rose is a rose? A poem is a poem?

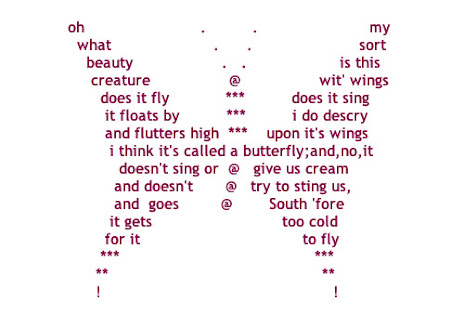

by David Schondelmeyer

The Mouse's Tale, by Lewis Carroll

Fury said to a mouse

that he met in the

house, "Let us

both go to law:

I will prosecute

you.-- Come, I'll

take no denial;

We must have

a trial: For

really this

morning I've

nothing to do."

Said the mouse

to the cur,

"Such a trial,

dear Sir, with

no jury or

judge, would

be wasting

our breath."

"I'll be

judge, I'll

be jury,"

Said cunning

old Fury:

"I'll try

the whole

cause, and

condemn

you

to

death."

"The Mouse's Tale" by Lewis Carroll offers a playful critique of the judicial system. The poem emphasizes the need for a fair trial and the dangers of some kinds of authority. Lewis Carroll was an English author who is best remembered for his novels. It is a wonderful example of Carroll's wit and humor. As the Mouse tells his tale, Alice imagines the 'tale' as his 'tail', giving readers a glimpse into her imaginative personality.

The Mouse's Tale - Uncurled

Furysaidtoamouse,Thathemetinthehouse,'Letusbothgotolaw:Iwillprosecuteyou.Come,I'lltakenodenial;Wemusthaveatrial:ForreallythismorningI'venothingtodo.'Saidthemousetothecur,'Suchatrial,dearsir,Withnojuryorjudge,wouldbewastingourbreath.''I'llbejudge,I'llbejury,'SaidcunningoldFury;'I'lltrythewholecause,andcondemnyoutodeath.'

e. e. cummings

r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r

who

a)s w(e loo)k

upnowgath

PPEGORHRASS

eringint(o-

aThe):l

eA

!p:

S a

(r

rIvInG .gRrEaPsPhOs)

to

rea(be)rran(com)gi(e)ngly

,grasshopper;

The poet Edward Estlin Cummings (1894-1962) is known for his unconventional attitude to punctuation and typography: he famously styled himself as "e. e. cummings", all in lower case, and a number of his short poems can be considered examples of shaped or concrete poems. This poem is one of his most accomplished contributions to the form. As the name suggests, grasshoppers are known for their hopping and leaping, and here, the word ‘grasshopper’ itself jumps about the page until it finally settles down (onto the grass?) in the final line.

The real word appears only in the last line of the poem, which may be rearranged as follows:

The grasshopper who, as we look, is gathering up into a leap arriving to become (rearrangingly) a grasshopper.

It is difficult to perceive it: it is the same color as the grass, and leaps suddenly. But, in the end when it leaps, the observer may distinguish it. The motions of a grasshopper are suggested by various permutations of the letters of “grasshopper” and other typographical signs (parentheses, punctuation marks, and capitals). The layout enacts the experience of a person looking at it, who will only be able to see the grasshopper completely at the last line.

by John Hollander

Dusk

Above the

water hang the

loud

flies

Here

O so

gray

then

What A pale signal will appear

When Soon before its shadow fades

Where Here in this pool of opened eye

In us No Upon us As at the very edges

of where we take shape in the dark air

this object bares its image awakening

ripples of recognition that will

brush darkness up into light

even after this bird this hour both drift by atop the perfect sad instant now

already passing out of sight

toward yet-untroubled reflection

this image bears its object darkening

into memorial shades Scattered bits of

light No of water Or something across

water Breaking up No Being regathered

soon Yet by then a swan will have

gone Yes out of mind into what

vast

pale

hush

of a

place

past

sudden dark as

if a swan

The theme of this pram is change. The perfect moment is symbolized with the shape of Swan and Shadow. The poem’s tone is sad and lovely, imitated by the juxtaposition of phrases into a swan and its reflection, alone and beautiful. It even says that the swan leaves the vast pale hush of a place. The placing of the words also serves to imitate a call-and-response technique, answering the questions what, when, and where.

The image of a swan in Hollanders's poem is represented as a symbol of love. Possessing this quality, the swan's image is preserved in our consciousness as a special symbol of beauty. In literature and myth, the swan symbolizes light, purity, transformation, intuition, grace. In Ancient Greece the swan stood for the soul and was linked to Apollo, the god of the Sun, whereas in other religions, the swan became a feminine symbol of the moon.

The theme of the poem is to portray how a child gets excited and thrilled by his own shadow. The child is curious and wonders how the shadows keep changing for everyone. He is impressed by his own shadow and so he starts noticing everything about his shadow. This interpretation isn’t just for youngsters; the sentiment applies to all ages and experiences. In addition, a swan has often been seen as a symbol of wisdom and includes awakening the power of self, balance, grace, inner beauty, innocence, self-esteem, seeing into the future, understanding spiritual, evolution, developing intuitive abilities, and grace in dealing with others and commitment.

Exploration 1: Is a clutter of words and shapes, patterns and grammar-phobic writing, a poem?

Exploration 2: Do you think Shape Poems have a future?

Exploration 3: Name the Mouse below, write a (5-7-5) haiku about it, and submit to catherineastenzel@gmail.com For your efforts, you have a chance to win a fantastic prize, redeemable through Wannaskan Almanac’s Jack Pine Savage. You can’t win if you don’t play. The winner will be announced in two Monday blogs in February. Sharpen those pencils!

See you at the Fickle Pickle!

ReplyDelete1. Why not?

2. No one's going to prevent it.

3. The Orlandan mouse

Slips under the doors unseen

Snap! Missed him again

Your entry is noted and much appreciated, So far you are the only poet who has submitted, so get ready for that prize. Will wait another week before announcing. thanks for your submission!

DeleteI liked the butterfly!

ReplyDeleteSuch a generous collection in these two posts. I think of poems as crystallizations. These images do that both visually and through words. I bet your workshop was fun!

ReplyDeleteSo happy you enjoyed these unusual offerings. Remember to enter the competition with prize! You can't win if you don't play! Affectionately / JPS

Delete